Kennan Cable No. 88: Ukraine’s Plans for Demographic Recovery

The Ukrainian people are entering the third year of their fight for their existence as a state and people. Every day, soldiers and civilians—children, women, and the elderly—are killed, homes are destroyed, and jobs are lost. The uncertainty of wartime forces individuals, families, communities, and the authorities to shorten their planning horizons and be ready to adapt at a moment’s notice. Under such circumstances, any effort to develop long-term strategies focused on postwar development immediately raises questions of feasibility. However, no society can live by only looking at the challenges of the moment. The future is also important for collective survival. Today’s demographic crisis is a challenge that short- and long-term government strategy planning must account for.

Since Ukraine gained its independence in the 1990s, its demographic situation has demanded the government’s attention. Authorities worked to improve its policies and achieved some success between 2006 and 2015. Unfortunately, these positive outcomes were adversely impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and demolished by Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022. In recent months, the Ministry of Social Policy prepared a plan to respond to the demographic challenges brought on by the war. This document, the Demographic Development Strategy, underwent a series of public discussions and was developed in cooperation with government officials, Ukrainian scholars, and specialists from several international organizations. The strategy was finalized in January 2024 and now waits for governmental approval.

About the Demographic Development Strategy

The new strategy envisages two basic scenarios for Ukraine’s development. The inertia scenario assumes that demographic processes will evolve naturally, without government intrusion. It predicts that the population of Ukraine within its 1991 borders may decrease to 28.9 million people by January 2041, and to 25.2 million by January 2051. The guided scenario assumes the implementation of the Demographic Development Strategy and predicts the achievement of decent living standards for Ukrainians returning from abroad. Under this scenario, the demographic decline would be mitigated, with estimates of a population of 33.9 million by January 1941, and 31.6 million by January 2051.

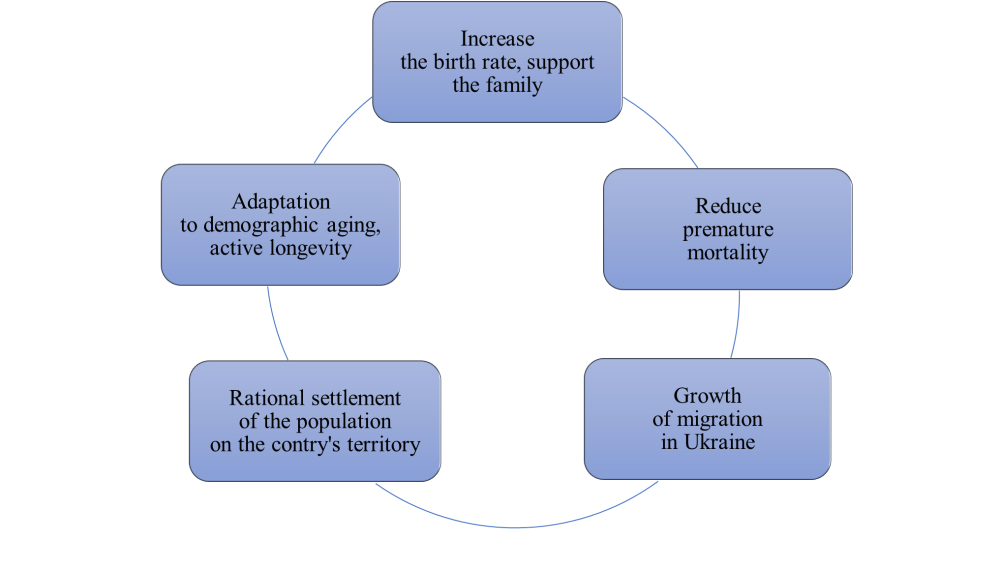

The goal of the strategy is to ensure that the population maintains its long-term reproduction capacity despite all war-related conditions. It is intended to improve Ukraine’s sociodemographic characteristics as defined in the policy’s five strategic goals:

Chart 1. Goals of the Demographic Development Strategy of Ukraine (2024–2040)

The strategy proposes using tested—both in Ukraine and worldwide—policy instruments to avoid the inertia scenario. These include policies intended to improve the birth rate; reduce premature mortality and excessive migration; address population displacement; accommodate an aging population; and address other challenges confronting the nation.

Increasing Ukraine’s Birth Rate

The primary issue that the strategy addresses is Ukraine’s population size, an issue greatly exacerbated by Russia’s aggression and occupation of Ukrainian territory. The war both sharply reduced Ukraine’s already low birth rate, and sharply raised mortality across all age groups and occupations. Several million displaced Ukrainians moved toward the western part of Ukraine, and over six million others, mainly children and women, were forced to leave the country. In addition to the refugees, large-scale labor migration abroad between 2022 and 2023 threatens to turn into permanent emigration over time. The illegal annexation of Crimea and some southeastern Ukrainian regions between 2014 and 2022 has affected the demographic situation as well.[1] As a result, according to our calculations, Ukraine’s population has radically decreased, moving from 48.5 million inhabitants in December 2001, to 42.0 million in January 2022, and then to 36.3 in August 2023 (of which, only around 31.5 million reside in the government-controlled territories).[2]

Since Ukraine has not conducted a census since 2001, analysts must use both conventional and unconventional sources (as explained in the endnote 2). But making forecasts about the population size in the future is even more difficult. First, there is a lack of information on the population of the temporarily occupied territories and areas near the front. Second, military development scenarios vary greatly, which directly impact any demographic assessment. Third, the decisions that displaced and migrated Ukrainians make about whether and when to return are difficult to predict. Any demographic strategy must take all this into account in planning for the country’s development.

Even in peacetime, Ukraine’s fertility rates have been below the level required for population replacement (2.2) since the mid-1960s. In 2021, the total fertility rate was 1.2. Put another way, the number of children born that year was half the number of people who reached the age of 60. After the start of Russian aggression in 2022, the fertility rate fell below 1.0.

Even if the war were to end tomorrow, Ukraine would face an extreme challenge in improving its birth rate. There are five major reasons for such a low birth rate. First, there was a change in social values, towards self-realization and individualism. This translated into a shift from the number of children born to the quality of their care and upbringing, as well as a modification in the forms of marriage and the age at which people became parents.

Second, economic factors played a negative role. According to 2021 statistical data, the poverty rate in Ukraine was 20.6 percent in the general population. For families with children, however, it was higher, measuring 22.4 percent for families with children; 27.6 percent for families with children under three years old; and 53.6 percent for large families. With the outbreak of the full-scale Russian invasion, these numbers became even worse.

Third, there are structural obstacles to combining work with raising families for women in Ukraine. There is a significant difference in employment levels for women between 25 and 44 years old in 2021: the employment rate was 71.1 percent for women without children and only 51.5 percent for women with children between three and five years old. During the war, the shelling and large-scale destruction decreased the opportunities for children to attend school, which significantly worsened employment opportunities for women.

Fourth, public health in Ukraine has deteriorated considerably in recent years, including declining trends in reproductive health. Additionally, Ukrainian women live under stress and depression caused by constant fear for their lives and the lives of their children and relatives.

Finally, the fifth factor is the separation of families. Many men have been drafted into the armed forces, while many women have migrated abroad.

Together, these factors have a synergistic effect, forcing most Ukrainian families to postpone childbearing in anticipation of a more favorable period. A significant number of these postponed births may never materialize.

In the past, the Ukrainian government tried to increase the birth rate by increasing maternity benefits for women until their children reach the age of three. The government increased these benefits tenfold in 2005, and then threefold in 2008. These increases succeeded in increasing the birth rate: in 2005, there were 426,100 children born, compared to 512,500 newborns in 2009. However, the effect of financial incentives on the fertility rate was rather short-lived and mainly influenced families with low levels of education and income. A much more lasting positive result was achieved through the reduction of poverty for families with children, the creation of a legal and policy environment friendly to such families, and an increase in the economic self-sufficiency of families.

Reducing Premature Mortality

The second most important cause of the demographic crisis is high premature mortality for people under 65, an issue especially affecting men. Even before the major invasion and the COVID-19 pandemic, by 2020, the average life expectancy in Ukraine was 71.3 years, the lowest rate in Europe.

The new strategy identifies the main factors contributing to the excessive mortality in Ukraine as a low level of hygiene culture, the prevalence of dangerous working conditions, unhealthy lifestyle, late response to health issues, widespread vaccination hesitancy, and faults in the public health care system. Lack of access to medical and recreational services are especially acute for residents in small towns and villages.

The gender gap in mortality is typically high for all post-Soviet countries. According to 2020 official statistics, the gender gap in life expectancy was 9.8 years: 76.2 years for women and 66.4 years for men. Male mortality in Ukraine was higher than female mortality in all age groups, but especially—more than three times—in the 25–34 cohort. After retirement, this gap decreases. This difference stems from variations in lifestyle for women and men, and the exposure of men to more dangerous employment conditions.

Russia’s full-scale aggression has significantly increased mortality rates for Ukrainians. This is especially noticeable among soldiers who are risking death in battles and captivity. At the same time, the general population also risks death on a daily basis from rocket and drone attacks, limited access to medical care in the temporarily occupied territories,[3] and extreme stress that can lead to the emergence of new and exacerbation of old chronic diseases. Even though there are currently no reliable data on human losses among Ukrainian military personnel and civilians, the toll has tragically reduced the population.

The cessation of hostilities in Ukraine is undoubtedly the first step to reducing mortality. However, the experience of other postwar countries shows that even the end of armed conflict does not immediately return mortality to prewar levels.

Addressing Migration

Out-migration of Ukraine’s population has long exceeded in-migration since the dissolution of the USSR. For economic reasons, Ukrainians have been leaving for Russia, then for Poland. On the eve of the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of Ukrainian labor migrants abroad was estimated at between 2.5 and 3 million people. Over the last decade, Ukrainians consistently were among the top nationalities receiving first-time EU residence permits. For example, 873,700 Ukrainian citizens received EU residence permits in 2021, 30 percent of all those issued.

Russia’s military aggression has resulted in the largest outward flow of migration from Ukrainian territory since WWII. Millions of people moved away from frontline areas to either relatively safe regions of Ukraine or to other countries. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) data, by the end of 2023, over six million Ukrainians fled abroad. Of these, 1.2 million were either deported to or (less often) voluntarily left for the Russian Federation.[4] According to Eurostat, by the end of October 2023, 63.2 percent of the 4.3 million Ukrainians who were in the EU/European Free Trade Zone (excluding Hungary) were women, 33.2 percent were under the age of 18, and 6.1 percent were 60 or older.[5] Since one-third of forced migrants abroad are children and adolescents, their non-return may cause irreparable demographic loss for Ukraine.

The situation is potentially made worse if some Ukrainian families decide to reunite outside Ukraine after the war ends. As a recent study demonstrates, many migrants may not return home.[6] Female migrants who have found good jobs and housing outside of their country may bring their husbands to join them once martial law and travel restrictions are lifted in Ukraine. Additionally, growing divorce rates between partners separated by war reduce the incentive of Ukrainian women to return home after the war.

The same study shows that the reasons for Ukrainians’ reluctance to return home include uncertainty about security in Ukraine (for 47 percent of those polled), lack of workplace or place to live (31 percent), insufficient access to basic services (22 percent), and lack of acceptable quality of education for children (15 percent). Abroad, Ukrainian migrants value stable employment (21 percent), school and preschool institutions (11 percent), and a sense of integration (11 percent).[7]

The new strategy includes policies to attract Ukrainians living abroad so they return to their homeland. These policies would apply to migrants who left because of war and those who moved before the war. Should conditions require it, the strategy also includes migration policies to attract immigrants from other countries.

(Re)distributing Postwar Population

The military conflict has greatly influenced population distribution in Ukraine’s regions. The first cohort of internally displaced people (IDP) appeared in Ukraine in 2014 following Russia’s annexation of Crimea and instigation of separatist conflicts in Donetsk and Luhansk. These attacks caused approximately 1.5 million Ukrainians to leave their homes for safer regions in the country. In December 2023, the number of IDPs reached 4.9 million. These numbers include about 739,000 families with children that were forced to leave their homes for regions of Ukraine away from the front lines. Despite efforts from the government and local communities, IDPs lack housing, acceptable work and income, and access to timely health and social assistance. The constant stress and uncertainty about their future cause larger declines in fertility and increases in mortality among IDPs compared to the general population.

At the same time, the massive population movements within Ukraine can be a source of labor resources for the regions where IDPs settle in. The demographic strategy envisages the formation of a new resettlement system to influence and support the reconstruction of different regions of Ukraine. The most likely scenario for postwar development envisions the formation of five territorial clusters.

The central cluster includes relatively safe regions of central Ukraine that already shelter the largest number of IDPs. This cluster is likely to become the country’s new industrial center after the war.

Due to its closeness to the EU, the western cluster will need a larger workforce. This region will develop quickly through economic ties with the European countries and will provide a strategic location for military industry. However, western Ukraine has long been underdeveloped relative to other major population centers. It will take time and investment for this region to accommodate a large population influx.

The northeastern territories will remain the area of the most “insecure habitation” due to its proximity to Russia. Economic development in these regions will require special policies and interventions from both the central and local governments.

The southern cluster’s prospects are currently the least clear. This area will probably have to develop under conditions of both constant threat from Russian and the benefits from sea-born trade.

Ukraine’s large urban environments—like those in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odessa, Dnipro, Lviv, Donetsk, and Zaporizhzhia—will constitute a separate cluster. Big cities will likely provide the most accessible services and job opportunities to their residents.

Rational population (re)settlement in postwar Ukraine must plan for housing (including temporary housing during reconstruction), infrastructure, reindustrialization, and job creation. These plans must also include social infrastructure, including hospitals, schools, and other public buildings in each of the clusters.

Adapting to an Aging Society

Ukraine has one of the 30 oldest populations in the world: almost 18 percent of its population is older than 65. Over the next several decades it will age even more. According to projections, the over-65 proportion will reach 21 percent by January 2041, and it will reach 23 percent of the general population by January 2051. This means that Ukraine must adapt and address issues related to the lives of older people.

The demographic strategy plans to promote and accommodate the increased longevity of the Ukrainian population. The quality of life of older Ukrainians will depend on general factors like the social and economic outcomes of the war and specific factors like pensions; accessibility of social support and health services, especially in rural areas; and opportunities for employment and participation in society. Improving the quality of life of the elderly is an essential component for improving Ukraine’s post-war prospects.

Creating a Supportive Environment for Demographic Improvement

Improving a nation’s demographic trends both requires and drives progress in other social sectors. For example, demography determines a nation’s social and economic prospects, while governmental policies impact long-term demographic processes. The new Demographic Development Strategy, based on surveys and research, proposes to help develop an environment which supports population growth. Such an environment—in both war and postwar periods—has four major components: basic security, proper housing, a balanced labor market, and supportive living conditions.

In the framework of this strategy, basic security for Ukraine’s population means achieving physical security (advanced air defense system, accessible bomb shelters, and de-mining) and emotional security (social trust and trust in the authorities, supportive information flows, de-polarization). The solution to the housing problem means reconstruction and construction of a mix of private and public housing, using the best models from Ukraine and around the world. The labor market will require the elimination of imbalances that impede the ability of public and private enterprises to resume their operations and efficiently employ human resources. Finally, supportive living conditions mean the provision of basic services, including access to clean water, electricity, heat, communications systems, and public transportation.

Conclusion

Since the war continues with no end in sight, preventing the implementation of the Demographic Development Strategy, the authorities must use short-term approaches for wartime problems. However, these short-term solutions should take into consideration the goals and requirements of the demographic strategy, starting with building public understanding and support for its objectives. These strategic objectives will need to be regularly reviewed and, if necessary, adjusted, should the war bring new losses to the Ukrainian nation. That way, Ukraine will be ready to rebuild when the war ends.

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Endnotes

[1] For more on this, see Ella Libanova, “Ukraine’s Demography in the Second Year of the Full-Fledged War,” Focus Ukraine, June 27, 2023, https://www.wilsoncenter.org/blog-post/ukraines-demography-second-year-full-fledged-war.

[2] It is very difficult to determine a reliable count of the country’s population, since there were no census conducted in the recent years. This document uses the estimate of the population during the war was made by researchers from the Ptukha Institute for Demography and Social Studies of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. They used the following sources: the State Statistics Service (on population before the full-scale war); mobile operators (the number and location of their clients); the Ministry of Justice (registered deaths and births); the Ministry of Health (the number of newborns and children registered with the medical authorities); the Ministry of Social Policy (the number and location of IDPs); the International Organization for Migration (recent surveys); the UNHCR (the number, demographic characteristics, and regions of origin of Ukrainian forced external migrants abroad); the Pension Fund of Ukraine (the number and gender/age composition of retired people); and the Ministry of Education and Science (the number, location, and gender/age composition of students in educational institutions of different levels).

[3] According to the Ministry of Public Health of Ukraine, during the battles, 189 medical facilities were destroyed and another 1,427 severely damaged in the temporarily occupied territory.

[4] “UNHCR Warns Worsening Conditions and Challenges Facing Vulnerable Ukrainian Refugees in Europe,” press release, UN Refugee Agency, November 15, 2023, https://www.unhcr.org/news/press-releases/unhcr-warns-worsening-conditions-and-challenges-facing-vulnerable-ukrainian.

[5] See Eurostat’s constantly updated database at https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/migration-asylum/asylum/database?node_code=migr_asytp.

[6] According to the Center for Economic Strategy, in the spring of 2023, only 63 percent of respondents planned to return to Ukraine. About 14 percent of those migrated people did not plan to return, and 23 percent were undecided. It is safe to estimate that the number of Ukrainians who will remain abroad will range from 1.3 million to 3.3 million, depending on further developments in the situation. See Гліб Вишлінський, Дарія Михайлишина, Максим Самойлюк та Марія Томіліна, Біженці з України: хто вони, скільки їх та як їх повернути?, Центр економічної стратегії, (“Refugees from Ukraine: Who Are They, How Many Are There and How to Return Them?” March 21, 2023), https://ces.org.ua/who-are-ukrainian-refugee-research/.

[7] For example, see «Передумови повернення в Україну для участі у відбудові українських жінок, які знайшли тимчасовий прихисток за кордоном» (Ukrainian Women’s Congress, “Study ‘Prerequisites for Returning to Ukraine to Participate in the Reconstruction of Ukrainian Women Who Found Temporary Shelter Abroad,’” December 3, 2023), https://womenua.today/news/doslidzhennya-peredumovy-povernennya-v-ukrai-nu-dlya-uchasti-i-vidbudovi-ukrai-nskyh-zhinok-yaki-znay-shly-tymchasovyy-pryhystok-za-kordonom-povnyj-zvit/.

Author

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Kennan Institute is the premier US center for advanced research on Eurasia and the oldest and largest regional program at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Mexico Is Growing Old. Can It Build a Care System in Time?

Demographic Trends Present Risks and Opportunities - Wilson Quarterly Summer 2024

The Workforce of the Future