A blog of the Kennan Institute

“The war, which we are trying to stop, which was launched against us using the Ukrainian people....” At a recent G20 event in India the audience laughed at these remarks by Sergei Lavrov, Russia’s foreign minister. For those who do not live in an upside-down world, this phrase may indeed sound funny in its blatant disregard for the truth.

But to those who know Russia well this is not funny. The notion of Russia as a victim of a war waged against it is the official narrative disseminated in all seriousness by its chief propagandist, Vladimir Putin. He regularly, in different versions, repeats these words: “They were the ones who started this war, while we are using force to stop it.” The original wording of this phrase belongs to none other than Vladimir Zelensky, who, in his 2019 inaugural address, said this: “We are not the ones who have started this war. But we are the ones who have to finish it.”

If you think about it, the idea of Russia as a victim must sound outlandish, especially when uttered by someone who believes that might makes right and that Russia is a mighty nuclear power that cannot be defeated militarily. And yet lots of Russians keep listening and agreeing that Russia is both the unfortunate victim of the insidious and powerful West and a great power ready to bury the weak and degrading West. There are two unavoidable parts to almost every Putin speech—the first, in which he whines about how Russia has been wronged, and the second, in which he threatens the world with Russia’s power.

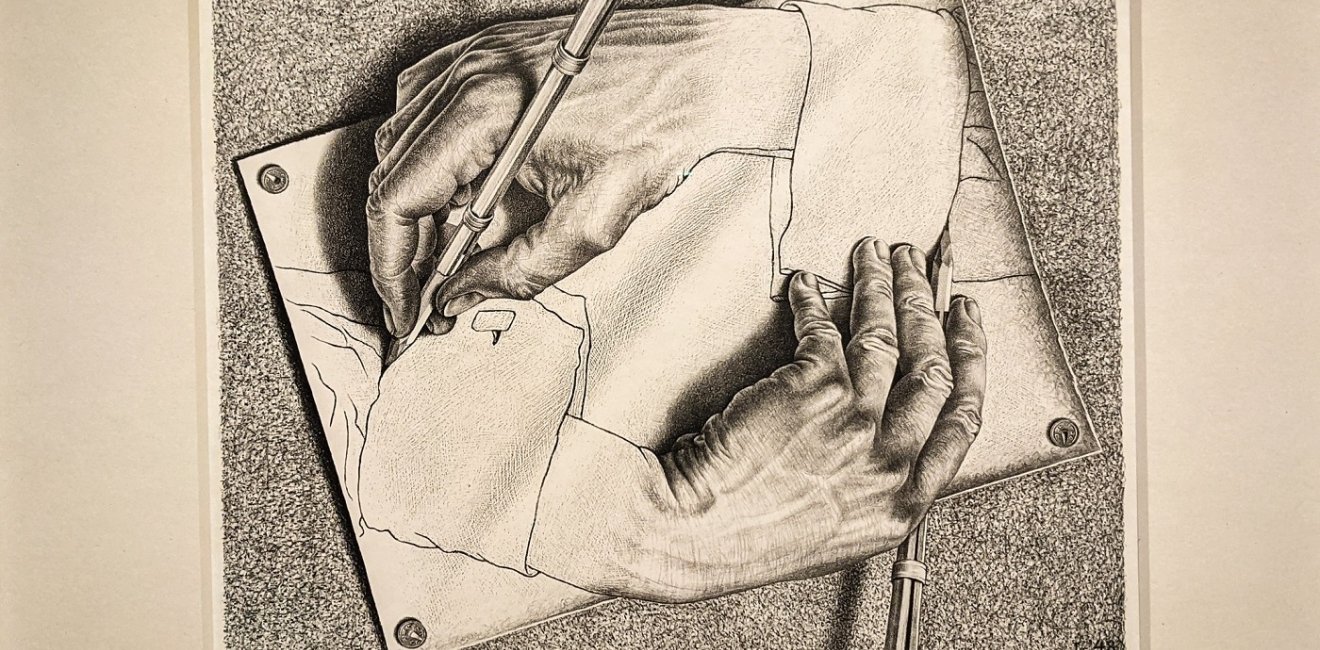

Logical contradictions, deception, manipulation of facts, refusal to call things by their proper names, and projecting onto others what they accuse you of are all tools Putin uses to shape reality. Even though the pictures he creates for his listeners could be compared to the impossible spaces in M. C. Escher’s engravings, we are all hostages to his world because the wars he wages are quite real. Though he explains to his audiences that he does not wage them.

Yes, in his depiction, Putin is both waging and not waging a war. Putin does not call what he started in Ukraine a war but a “special military operation.” He only uses the word “war” to describe what—in his mind—others are doing. The same applies to the words “aggression” or “blitzkrieg” ("the West’s economic blitzkrieg failed”). Putin seeks to end this war and for this purpose is conducting a “special military operation” and will continue to do so until it is over. That is, in translation, he will wage war until he finishes waging war.

Russia both bears and does not bear war-related losses. The authorities do not deny that people die while performing “special operation tasks,” but they do not publicize losses or even laud the heroes. A lot of the mobilized are from faraway provinces. The strategy is to spread the losses as thinly as possible across the country. Low-profile memorial services are held from time to time but only at the regional level. In his speeches, Putin speaks only about the benefits of the “special operation.” Troops are entitled to regular vacations and medical treatment, which will be paid for out of a special sovereign fund. According to Putin, people who have “worked” in the "special operation” must form the government’s personnel reserve.

Russia is both mobilizing and not mobilizing. Last year’s mobilization decree has not been revoked. According to Putin, the mobilization is over, but his words are not legally binding. Realizing that mobilization—particularly when it is called that—is unpopular, the authorities are doing everything to conduct it covertly. A creeping campaign, spread through the country continues. Regular conscripts who are not supposed to serve on the battlefields are pushed or forced to sign contracts with the military, thus replenishing the Russian force deployed in Ukraine.

Private military companies both exist and do not exist in Russia. The Wagner military company was until recently allowed to recruit in prisons. Now it is recruiting in sports clubs. Nothing like this would be possible in Russia without a directive from the highest authority, but no such directive has been published. The prisoners who have served on the front and survived were pardoned by presidential decrees, but the decrees were not published. Neither the famous Wagner military company nor any of the other, lesser-known companies can exist, according to Russian law, which expressly bans mercenary activity.

Martial law is both in effect and not in effect in Russia. In a recent decree, Putin, referring to the law on martial law, ordered that those companies that fail to deliver on defense contracts be placed under external administration. Last October, Putin imposed martial law on four regions of Ukraine illegally annexed by Russia. But the new decree in no way implies that it concerns only these four “regions” of the Russian Federation. At the same time, Putin did not announce the introduction of martial law in the entire country if only because in this case, it would have been necessary to call a war a war.

Examples of this kind are endless. This is a special sort of language, a language of eluding responsibility. In Russia’s official discourse, what Russia is doing in Ukraine is both a tragedy caused by the actions of others and a necessary action taken by Russia. “The current situation is our common tragedy,” Putin said of Russia’s war against Ukraine. That tragedy, according to him, is caused by the policies of “third countries.” In other speeches, Putin presents his “special operation” as a momentous, pivotal event. He speaks of the past year, 2022, as the time of “necessary decisions, the most important steps toward gaining full sovereignty for Russia and a powerful consolidation of our society.” That is, he is both responsible for what is happening (if he presents it as a good thing) and not responsible for it (if he presents it as a bad thing).

A desire to avoid responsibility for bad things and attribute good things to ourselves is natural. It is not a skill that needs to be taught. In childhood and adolescence, we all go through this developmental stage in one way or another (“it wasn't me”). It is not walking away from responsibility that needs mastering but taking it on.

We are witnessing a striking phenomenon. Millions of people listen, spellbound, to someone who, in every single public speech, twists and turns like a teenager caught doing something shameful. All of the features of speech behavior described above are characteristic of immature people who have done bad things and then try to pretend that what is happening has nothing to do with them. This would be funny if it were not sad, just like Lavrov’s words about “the war that was launched against us.”

Русская версия данной статьи была опубликована в проекте «Иными словами».

The opinions expressed in this article are those solely of the author and do not reflect the views of the Kennan Institute.

Author

Editor-at-Large, Meduza

Kennan Institute

After more than 50 years as a vital part of the Wilson Center legacy, the Kennan Institute has become an independent think tank. You can find the current website for the Kennan Institute at kennaninstitute.org. Please look for future announcements about partnership activities between the Wilson Center and the Kennan Institute at Wilson Center Press Room. The Wilson Center is proud of its historic connection to the Kennan Institute and looks forward to supporting its activities as an independent center of knowledge. The Kennan Institute is committed to improving American understanding of Russia, Ukraine, Central Asia, the South Caucasus, and the surrounding region through research and exchange. Read more

Explore More in The Russia File

Browse The Russia File

Chechnya as a Model of Modern Russia

Russia’s Indigenous Communities and the War in Ukraine

Gas and Power in a Changing US–Russia Relationship