Secretary of State Marco Rubio is traveling to Central America and the Caribbean. That is welcome news for smaller countries that typically struggle to get the attention of Washington.

Usually, new secretaries of state reserve their first overseas visits for major US allies in Europe or Asia. Or perhaps for our neighbors, Canada and Mexico. So it is noteworthy that Rubio is focusing attention on El Salvador, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Guatemala, and Panama, with a combined population not much larger than that of California. What explains his unusual itinerary?

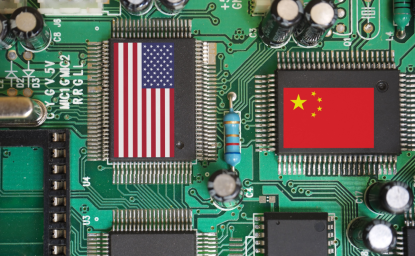

For one, China’s growing presence in the region and its control of two strategically located ports by the Panama Canal will certainly figure on Rubio’s agenda. Immigration is another factor in the decision to visit the US “near abroad.” Guatemala and El Salvador are significant sources of migrants to the United States and President Trump has prioritized efforts to accelerate deportations and discourage new arrivals.

But another topic should also be high among Rubio’s talking points–the nearshoring of regional supply chains.

Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic are healthy economies that are not significant sources of irregular migration. Rather, these two nations, together with Panama, are the founding members of the Alliance for Development in Democracy (ADD), a bloc designed in part to attract nearshoring investment. All three are stable democracies, boasting open, dynamic economies. All three enjoy free trade agreements with the United States. All three value close diplomatic relations with Washington.

“China’s growing presence in the region and its control of two strategically located ports by the Panama Canal will certainly figure on Rubio’s agenda. Immigration is another factor. But another topic should also be high among Rubio’s talking points–the nearshoring of regional supply chains.”

Just as significant as the countries on Rubio’s itinerary are those Central American nations he will avoid, Nicaragua and Honduras, where leaders are hostile to the United States and friendly to Venezuela. The signal is clear: the Trump administration will work with countries aligned with its values. Others should expect the cold shoulder, or worse.

The question is what friendly countries should expect from the new administration. In 2022, the ADD countries signed an agreement with the State Department that recognized, “it is in the economic and national security interests of the United States and the ADD countries to ensure their supply chains are transparent, secure, sustainable, and diverse.”

The accord called for dialogue on economic growth and supply chain partnerships and subsequent negotiations explored investment and trade opportunities in sectors such as biotechnology and pharmaceuticals, information technology and microprocessors, and advanced manufacturing and automotive parts. Textiles and apparel and agriculture were also sectors of interest. The Dominican Republic and Costa Rica also offer US firms back office services, call centers, and software development.

To reduce its dependency on revenues from the Panama Canal, Panama is looking to expand its role in global supply chains. Its government has issued regulations to improve its investment climate and bolster physical and digital infrastructure. Like Costa Rica, it has received US support to play a role in the computer chip industry. Costa Rica and the Dominican Republic each employ over 200,000 workers in free trade zones. Guatemala, Central America’s biggest economy, might join the ADD.

“There is uncertainty as to whether the new US authorities will continue promoting nearshoring, rather than push US firms to bring jobs from China exclusively to the United States.”

Even so, there is uncertainty as to whether the new US authorities will continue promoting nearshoring, rather than push US firms to bring jobs from China exclusively to the United States. That would be a mistake. Further expansion of supply chains in Latin America, including in the ADD countries, is the best strategy for addressing the factors that contribute to migration: debilitating poverty and a shortage of good job opportunities.

Regardless of US preferences, there are links in the modern supply chain that will not return to American soil. In low-productivity jobs, US workers are simply too expensive, and too few are willing to labor on assembly lines. By contrast, this is a golden age for regional economic integration. Increasingly, experts see nearshoring as the best option for helping US companies make their supply chains–disrupted in recent years by the pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine–resilient, secure, and cost-competitive.

There is another reason for the Trump administration to consider nearshoring. The region depends heavily on remittances sent by migrants in the United States. As many of those migrants are sent home, those remittances will dry up. Earnings from nearshoring, in new exports and jobs, could compensate for the decline in cash transfers and prevent economic trauma that would increase migration.

Expressing continued US support for nearshoring would be reassuring, but Rubio should do more, communicating a vision for how to promote US investments and commerce in the region. Countries such as Guatemala need technical assistance to improve the business climate, and financing, including from multilateral development banks, for better roads, railways, bridges, and ports, reliable, clean, and affordable energy, and to create a skilled workforce.

“Expressing continued US support for nearshoring would be reassuring, but Rubio should do more, communicating a vision for how to promote US investments and commerce in the region.”

In the Caribbean, moreover, nearshoring is the best strategy for competing with China. It is not enough to discourage governments, desperate for investment and new export markets, from partnerships with China. The United States must instead offer attractive alternative arrangements that would create jobs and generate economic growth.

The destinies of the United States and its Central American and Caribbean neighbors are intertwined. The knitting together of supply chains would construct a web of prosperity, reducing irregular migration, bolstering the competitiveness of American business, and demonstrating that strategic cooperation with the United States, not China, is the path to sustainable economic growth.

Author

Professor Emeritus, University of California, San Diego; Former Senior Director for Inter-American Affairs at the National Security Council

Latin America Program

The Wilson Center’s prestigious Latin America Program provides non-partisan expertise to a broad community of decision makers in the United States and Latin America on critical policy issues facing the Hemisphere. The Program provides insightful and actionable research for policymakers, private sector leaders, journalists, and public intellectuals in the United States and Latin America. To bridge the gap between scholarship and policy action, it fosters new inquiry, sponsors high-level public and private meetings among multiple stakeholders, and explores policy options to improve outcomes for citizens throughout the Americas. Drawing on the Wilson Center’s strength as the nation’s key non-partisan policy forum, the Program serves as a trusted source of analysis and a vital point of contact between the worlds of scholarship and action. Read more

Brazil Institute

The Brazil Institute—the only country-specific policy institution focused on Brazil in Washington—aims to deepen understanding of Brazil’s complex landscape and strengthen relations between Brazilian and US institutions across all sectors. Read more