Explainer: U.S. Strategy to Defeat ISIS

An interview with Michael R. Gordon, author of "Degrade and Destroy: The Inside Story of the War Against the Islamic State, from Barack Obama to Donald Trump."

An interview with Michael R. Gordon, author of "Degrade and Destroy: The Inside Story of the War Against the Islamic State, from Barack Obama to Donald Trump."

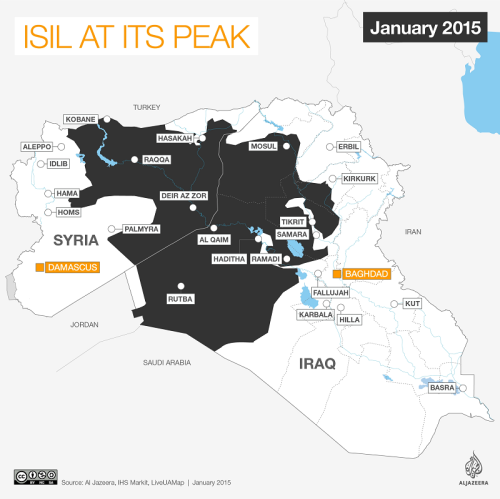

The U.S. had no advance strategy for how to deal with this new terrorist phenomenon. The Obama administration had not anticipated fighting a war with ISIS in Syria and Iraq, although the Special Operations community, including the Delta Force commander at the time, Colonel Chris Donahue, recognized a potential threat. So the rapid fall of Mosul in June 2014 came as a huge shock to the White House.

The U.S. strategy took a couple of years to flesh out and fully put in place. President Obama decreed that American troops would not engage in ground combat. The fighting on the ground would instead be carried out by local partners, namely the Iraqi security forces, the Kurdish Peshmerga and, as it turned out, the YPG, the Syrian Kurdish fighters who later dubbed themselves the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). In one of its first decisions, Washington sent military advisors to Iraqi bases to mentor Iraqi forces. But U.S. advisers were not cleared to accompany Iraqi battalions on the battlefield until the summer of 2016, and the advisers’ authorities were not fully expanded until the end of the Obama administration. As the strategy evolved, U.S. airstrikes also hit targets beyond the front lines, including ISIS command-and-control centers and financial targets, such as the militants’ banks.

The U.S. campaign was unique because it spanned two countries, involved work with disparate partners on the ground and entailed the extensive use of air power and in-depth intelligence. The scale of the U.S. effort to mentor and support its partner forces in Operation Inherent Resolve against ISIS was different than anything the United States had done elsewhere. The American footprint was far smaller compared to Operational Desert Storm to liberate Kuwait from Iraq in 1991 and Operation Iraqi Freedom in 2003 to oust President Saddam Hussein.

Of course, every conflict is different, but Operation Inherent Resolve offered several lessons. First, American politicians and the public generally want to avoid sending tens of thousands of troops back to the Middle East to fight terrorist militias, as the United States did after 9/11. So the United States opted to take on ISIS with a vast array of partners, some of whom didn't get along with one another. U.S. advisers were the glue that held them together.

Second, the Pentagon cannot confine its military advisers to large bases. They need to accompany partners on the ground, not merely to understand the battlefield, adapt strategy, and call in airstrikes, but also to share the burdens and risks. When partners are suffering most of the casualties and deaths, you can't order them around. You have to guide and influence them, which requires credibility that has to be earned.

Third, airpower has a big role, both to provide air cover for the U.S. partners, but also to target the enemy’s weak points in terms of command-and-control, finances, and fuel and other essentials. In terms of munitions, the United States used so many air-delivered munitions that it ran low on Hellfire missiles.

Fourth, U.S. strategy needs to do more to reduce civilian casualties, notably in urban settings, which is one of the most difficult challenges in this type of conflict. In Mosul, for example, much of which was heavily damaged, civilians often got caught in the crossfire, sometimes because ISIS would not let them flee or used them as human shields. The risk of harming civilians was also elevated because of the large amount of firepower that was needed to keep partner forces moving forward.

The U.S. military knew Iraq, its infrastructure and forces from its eight-year occupation. It had rebuilt the Iraqi army after President Saddam Hussein was overthrown in 2003. When U.S. forces returned in 2014, the initial mission was to rehabilitate and retrain the various branches of the Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) to fight ISIS. They also had to be prepared for urban conflict because ISIS was embedded in Mosul and other towns and cities in northern and western Iraq.

Delta Force set up command centers in Erbil and Sulaymaniyah, the competing Kurdish power centers, because it had to work with both Kurdish factions. The Kurdish Peshmerga and Iraq’s forces, historic rivals, also might not have cooperated as extensively as they did without American advisors.

The United States didn’t have any presence in Syria when ISIS seized much of the northeastern part of the country in 2014. Washington had originally hoped that some of the Syrian opposition that was fighting the Assad regime since the Arab uprising in 2011 could be repurposed to fight ISIS. But that U.S. initiative failed. In August 2014, Chris Donahue, then the Delta Force commander in northern Iraq, met with General Mazloum Abdi, leader of a Syrian Kurdish group largely unknown to the Americans. That meeting led to a new alliance between the U.S. Special Operations community and the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Thousands of Syrian Arabs eventually joined the SDF. The collaboration continued through the Trump and Biden administrations.

Not as much as people think. During the presidential campaign in 2016, Trump proposed stepping up the air strikes and moving to “take out” ISIS family members, implying that he was going to change the rules of engagement. But once in office, the rules of engagement did not change. He did take a significantly different approach, however. Unlike Obama, Trump did not scrutinize the details of the military campaign. U.S. forces were more empowered as oversight diminished. Otherwise, the Trump administration essentially carried out the Obama strategy. The main exceptions were when Trump twice ordered U.S. troops out of Syria in 2018 and 2019, which led to a lot of initial confusion but not a full withdrawal. As of mid-2022, approximately 900 U.S. troops remained in northeastern Syria and at the al Tanf garrison in southeast Syria near the border with Iraq.

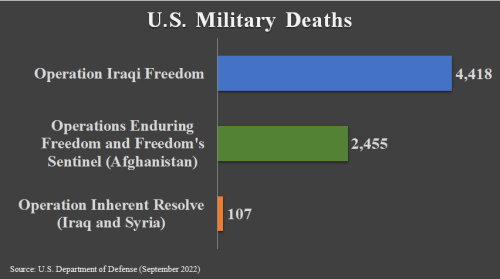

American casualties in the campaign against ISIS in Iraq and Syria were held to a minimum. A total of 107 Americans died between 2016 and 2022 in Operation Inherent Resolve, 20 of whom as a result of hostile action. In contrast, more than 4,400 Americans died in the invasion and occupation of Iraq between 2003 and 2011. More than 2,400 died in Afghanistan between 2001 and 2021. In Iraq and Syria, however, the U.S. partner forces paid an enormous price in the war against ISIS. The Iraqi Security Forces has lost thousands of troops. The SDF, according to one estimate, has lost some 5,000 fighters.

The character of the three wars differed. The invasion of Iraq in 2003 led to a lengthy eight-year occupation not anticipated by President Bush or his national security team. The 2001 intervention in Afghanistan led to a 20-year war which was also not anticipated either. In the fight against ISIS, Presidents Obama and Trump were clear that the United States was not going to engage in lengthy nation-building. The mission was to stabilize the areas, including de-mining and restoring essential services, but not to assume responsibility for governance or reconstruction of infrastructure. The burdens, costs and dangers of occupation were avoided, to the point that most Americans are probably not aware that Operation Inherent Resolve continues into fall 2022, even though the physical caliphate collapsed in 2019. Some 2,500 U.S. troops remained in Iraq and 900 in Syria.

Airpower was essential, though it was initially limited largely to supporting partner forces on the ground. The U.S. Air Force wanted to run a strategic campaign rather than just be the equivalent to flying artillery. General David Goldfein, who was then the Air Force Chief of Staff, suggested that the Air Force take over the counter-ISIS campaign from the Army generals. He did not win that battle, but the scope of the air campaign changed.

One major early operation, Tidal Wave II, targeted tanker trucks transporting oil used by ISIS both to supply and fund its forces. The Obama administration was concerned about civilian collateral damage amid arguments over whether truck drivers for ISIS should be considered civilians or co-belligerents. Over time, the air commanders did gain more authority over intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance to allow attacks on deeper targets. Small teams of advisors who moved with Iraqi troops also gained power to call in airstrikes previously coordinated from command centers in the rear. The expanded air campaign—targeting money, oil, and command and control, even in big cities such as Mosul—became more strategic.

The lesson was that a small number of U.S. advisors can harness enormous firepower. The combination of all these elements produced a potent force, even against a terrorist army that had armor, suicide car bombs, drones and entrenched positions.

In 2022, the Iraqi and Syrian forces, supported by the U.S. and other coalition members, were still mopping up. Iraqis launch sporadic operations against ISIS cells, but they still depend on U.S. intelligence to locate many targets. The Iraqi armed forces and a significant number of Iraqi officials have recognized that they need the U.S.-led coalition to continue mentoring and training, since the Iraqi military remains a work in progress. In Syria, the SDF carries out raids, and U.S. drones have targeted ISIS leaders.

The presence of American forces has always been politically sensitive. But in fall 2022, Washington appeared unlikely to withdraw its troops from either Iraq or Syria. The U.S. troop withdrawal from Iraq in 2011, which followed failed talks with Baghdad over a Status of Forces Agreement, interrupted the effort to train Iraqi forces at a time when the threat from jihadi militants accelerated rapidly. Nobody wants to see a repeat of that, particularly after Afghanistan.

Michael R. Gordon, national security correspondent at the Wall Street Journal, is the author of Degrade and Destroy: The Inside Story of the War Against the Islamic State, from Barack Obama to Donald Trump (2022).

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more