Explainer: The Islamic State in 2021

A year-end briefing by Cole Bunzel, a fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution.

A year-end briefing by Cole Bunzel, a fellow at Stanford University's Hoover Institution.

The Islamic State continues to be a highly active and lethal insurgent force in the Middle East, particularly in rural Iraq and Syria. These are the so-called “Iraq Province” and “al Sham Province,” though despite what these names might suggest they do not indicate territorial control. With minor exceptions, the group has not been able to hold territory in these areas since the fall of the border town of Baghouz in March 2019.

It is far less active in North Africa, with the exception of the Sinai Peninsula, where it operates under the name of the “Sinai Province.” In the Sinai, as in Iraq and Syria, the Islamic State does not administer territory but rather prosecutes a low-level insurgency in hopes of wearing down the enemy and, ultimately, seizing control and reconstituting the state that it purports to be. Iraq, Syria, and the Sinai are the three main hotspots for the Islamic State in the MENA region. More sporadic attacks can be observed in Yemen, Somalia, and Libya.

Of the three big areas, Iraq sees the most insurgent activity, which is not surprising given the group’s Iraqi origins and the Iraqi complexion of its leadership. The attacks include small-arms assaults, ambushes, roadside bombings, suicide bombings, assassinations, kidnappings, and acts of sabotage. The smaller kinds of attacks are the most common today. The targets vary by area, but generally speaking they are the different areas’ security forces, their perceived supporters/collaborators, and the broader population of Shiite and other non-Sunni Muslims, all of whom are deemed unbelievers and apostates.

The adopted strategy in these areas was detailed by the group in its official weekly newsletter al Naba, which drew a distinction between the stage of state-building (tamkin) and the stage of guerrilla warfare (harb al isabat). A decision was made during the collapse of the territorial caliphate to revert to guerrilla warfare. In the present stage, then, the objective is to inflict the utmost harm on the enemy so that he not only cedes ground but is so badly defeated as to be unable to return to the battlefield. This is a rather lofty aspiration and not one likely to be realized soon, given the current state of the group vis-à-vis its local enemies. That being said, the group’s persistence and resilience are remarkable.

In terms of attack numbers and casualties, the trendlines are somewhat down over the past year, but not to such a degree as to inspire confidence that the tide is turning. In the latest reports of the U.N. Security Council and the Department of Defense (namely, the U.N. sanctions monitoring team report and the lead Pentagon inspector general report), no one is doing victory laps. The Islamic State insurgency is presented as “entrenched” and in some ways poised to grow worse. According to the United Nations, there are still some 10,000 Islamic State fighters between Iraq and Syria, though the real number is anyone’s guess. (I would assume a somewhat lower number.)

Improving the economy and a more inclusive political system would diminish the Islamic State’s appeal to a considerable degree, but there has been little progress on these fronts. These are areas—I’m speaking here of the Sunni parts of Iraq and central and eastern Syria in particular—where economic conditions are poor, and the Sunni Arab population continues to feel alienated from and neglected by the powers that be.

In Iraq: There is some impressive reconstruction taking place in cities like Ramadi. But in general, we are talking about insecure areas with half-ruined cities and millions of displaced residents. The sense of neglect and discrimination by the Shiite-dominated government in Baghdad persists, and this is compounded by the presence in these areas of Iran-linked Shiite militias that treat the Sunni population as natural Islamic State supporters. On the positive side of the ledger, Sunni Arab parties made impressive gains in the most recent parliamentary elections, suggesting that Sunnis might be looking to the political process to address their grievances.

In Syria: The conflict is to a large extent frozen in a way that is not favorable to reconstruction or political inclusiveness. About two-thirds of the country is controlled by the Assad regime with the support of Russia and Iran-linked militias. The Idlib area in the northwest is controlled by Hayat Tahrir al Sham, a former al Qaeda affiliate. And parts of the north and northeast are under the authority of the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army, while much of the northeast and east is under the control of the U.S.-backed Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-led force with ties to the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK), a Kurdish opposition party that is banned in Turkey and the U.S. list of terrorist organizations.

The Islamic State is most active in Syria in the mostly regime-controlled central Syrian desert and the SDF controlled northeast. This is a complex security and political environment where the economy is poor and grievances among Sunni Arabs are high. So long as the conflict is frozen, it will be rife for exploitation by the Islamic State.

Judging by the data reported in the Islamic State’s al Naba newsletter, there have been fewer attacks in Iraq this year compared to last year. In 2020, the group claimed an average of 110 attacks and 207 casualties per month in Iraq, while thus far in 2021 it has claimed an average of 87 attacks and 149 casualties per month. The decline is somewhat encouraging, but this is still a high number of frequently occurring attacks. As the Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) recently noted, the group seems to be focusing on higher-profile attacks outside its safe havens, such as a January 21 double-suicide bombing in central Baghdad and a July 19 suicide bombing in Sadr city, each of which killed more than 30.

As in Iraq, attacks in Syria are also down according to the reports in al Naba. In 2020 the Islamic State claimed an average of 45 attacks and 95 casualties per month in Syria, while thus far in 2021 it has claimed an average of 31 attacks and 74 casualties. Complicating this data, however, is the fact that the Islamic State is known to underreport its attacks in the Syrian central desert. According to analysts Gregory Waters and Charlie Winter, the group claimed just 25 percent of attacks attributed to it by local actors in 2020, indicating a deliberate—and anomalous—pattern of undercounting, perhaps as part of a strategy to establish itself in the area without attracting too much attention.

Recent comments by the DIA suggest that we might not want to read too much into the observed decline in reported attacks in 2021. In September, the DIA observed “no notable changes to the group’s internal cohesiveness” in Syria and stated it is “poised to increase activity in the coming quarter after a period of recuperation and recovery.” Also discouraging in Syria is the continued presence of the al Hol detention facility in SDF-controlled territory. The camp holds some 60,000 men, women, and children, many of them with links to the Islamic State. There has been some progress toward repatriating the detainees, but it has not been enough. The camp remains a site of recruitment and radicalization with no end in sight.

The attack data indicate a similar if somewhat more pronounced pattern of decline. In 2020 the Islamic State claimed an average of 16 attacks and 40 casualties per month in the Sinai, while thus far in 2021 it has claimed an average of 9 attacks and 17 casualties. According to the United Nations, however, the Islamic State in Sinai is “resilient” and boasts between 500 and 1,200 fighters.

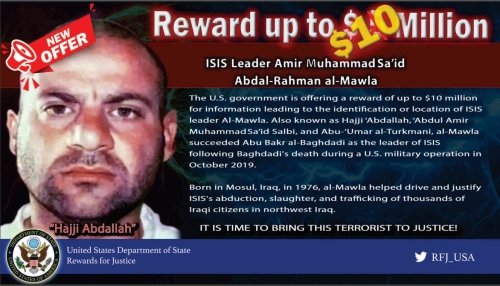

The Islamic State seems to have managed the transition from al Baghdadi to his successor al Mawla (aka Abu Ibrahim al Hashimi al Qurashi) fairly well. This is in part because the strategy of decentralizing the movement and returning to insurgency was set by al Bagdhadi and thus al Mawla has not had to reorient the group in any dramatic fashion. Another reason is that before his death in 2019 the Islamic State progressively deemphasized the centrality of al Baghdadi to the caliphate cause.

In 2014, when the caliphate was announced, al Baghdadi gave a televised sermon, revealing his face for the first time, and the group released a biography detailing his background and education. By contrast, al Mawla has not shown his face and the group has released almost no biographical details about him. Al Mawla has not even given an audio address in which Islamic State members might hear his voice—a sharp break in precedent. Some disaffected former members of the group have argued that it is contrary to the Sharia to pledge allegiance to a ghost, but that does not seem to have swayed opinion. If there was opposition to al Mawla’s ascension, it has not manifested on the battlefield.

Al Mawla has been a member of the Islamic State and its predecessors since the mid-2000s. He was hand-selected by al Baghdadi as his successor. Al Mawla was born in 1976 in Nineveh Province and grew up in Mosul, where his father was the imam of a mosque. He obtained a master’s degree in Islamic studies and used his scholarly credentials to ascend the ranks of the group as a religious judge. (He has been known as the “professor.”) He is known, as least in the dissident literature, as a particularly ruthless and heavy-handed leader.

The Treasury Department estimates that the Islamic State has tens of millions of dollars at its disposal, much of which is likely a legacy from the era before the return to insurgency. It is able to move money around through the hawala system and cryptocurrencies via hubs in Turkey and elsewhere. It generates new revenue through smuggling, extortion, looting, and ransoms. In Syria, for instance, Islamic State fighters are known to steal sheep in regime-controlled areas and smuggle them into SDF-controlled areas or across the border to Iraq, where they are sold in livestock markets. This sort of racket is not going to generate enormous cash flows for the militants, but their spending needs are far less today than they were when the group controlled vast swathes of territory. It is too soon to know whether the capture of the former finance chief will fundamentally affect Islamic State finances. Given the decentralized nature of the group now, the impact will likely be minimal.

In terms of destroying Islamic State capabilities, the main U.S. strategy is supporting partner forces in Iraq and Syria—namely, the Iraqi security forces and the SDF—with intelligence, advice, training, and air operations. In the case of Syria, the United States also conducts joint operations against Islamic State targets with the SDF. Both the Iraqi security forces and the SDF remain dependent on the United States for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) and airstrikes. The rapid breakdown of security in Iraq following the complete withdrawal of U.S. forces in 2011 served as a warning not to repeat the same mistake again.

Learn more about Hamas and how it relates to similarly aligned organizations throughout the region. Read more