After nearly two months of political paralysis, President Emmanuel Macron has appointed the veteran conservative politician Michel Barnier as France’s new prime minister to steer the country out of one of the worst political crises in the 66-year history of the Fifth Republic.

The recent parliamentary elections left France more divided than ever, with a fractured political landscape that some commentators say will make the country ungovernable. The New Popular Front, a four-party leftist coalition, won the most seats with 193 but fell well short of an absolute majority required to rule on its own. Macron’s centrist grouping lost some support and ended up with 166 seats, while the far-right National Rally party led by Marine Le Pen achieved substantial gains to control 142 seats. Barnier’s conservative party, known as Les Républicains or former Gaullists, came in fourth.

Despite his party’s weakened status, Barnier was chosen to serve as prime minister largely because he is considered one of the few political dealmakers in France capable of negotiating the painful compromises that will be necessary to govern. He served as minister in four previous governments as well as two terms as a European Union commissioner, but he is perhaps best known for crafting the intricate terms of Britain’s divorce from the EU while managing to keep a united front among the remaining 27 members.

But Barnier said he has no illusions about the struggle he faces in building an effective majority among such fiercely antagonistic factions. “We are in a grave moment,” Barnier said just before taking office. He promised to listen to and respect “all political forces” and avoid the kind of arrogance that has plagued Macron’s top-down presidency. “The government will not be so pretentious as to believe that it knows it all,” he said.

The New Popular Front challenged the legitimacy of Barnier’s appointment and vowed to bring him down with an early no-confidence vote. The Front insisted that it earned the right to form the next government after emerging as the largest political faction. But Macron, who as president holds singular authority in choosing the prime minister, rejected its candidate, Lucie Castets, a little-known civil servant in the Paris town hall.

“The election was stolen,” Jean-Luc Mélenchon, the founder of the hard-left France Unbowed party that is part of the New Popular Front, said in a televised speech. “We do not believe for one moment that a majority will be found in the National Assembly to accept such a denial of democracy.”

Macron had considered several candidates from both the right and left before settling on Barnier as his choice for prime minister. Barnier grew up in the Savoie region in the French Alps and earned acclaim for organizing the 1992 Winter Olympics in Albertville. He was first elected to parliament in 1978 and has long harbored presidential ambitions. After an unsuccessful bid to become the Republican candidate in the 2022 election against Macron, he has kept a low profile and seemed resigned to the likelihood that his political career was over. But friends say Barnier was rejuvenated when chosen by Macron despite the daunting challenges he faces.

With no political group close to controlling an absolute majority of 289 seats in France’s National Assembly, Barnier faces a tricky task in stitching together sufficient support for his policies, which will include approval of a new budget at a time of growing financial debt and economic uncertainty. With the left vowing to bring him down, Barnier will need at least tacit support from Le Pen’s party to sustain his new government.

Macron had called early legislative elections in July following the National Rally’s dominant showing in European elections. He hoped that French voters would be repelled by the prospect that the National Rally was close to entering government. The center and left political groups aligned to thwart far-right candidates wherever possible and Le Pen’s party failed to achieve its goal of an absolute majority, which at the time seemed to vindicate Macron’s gamble. But in the aftermath of political jockeying over the summer, it became clear that a new government will have to take account of the National Rally’s views to gain its acquiescence in blocking a no-confidence vote.

Barnier has already reached out to Le Pen to find common ground on ways to fight crime and illegal immigration. With the left vowing to bring Barnier down, his survival in office will depend on his ability to convince the National Front not to exercise its power of veto over his government.

Barnier reassured Macron and his allies that he will strive to protect their major economic reforms, such as raising the legal retirement age to 64 from 62 and reducing corporate taxes to stimulate jobs and growth, which the left had promised to reverse. Macron and Barnier also are fervent Europeanists, who are determined to combat Le Pen’s Euroscepticism including a previously stated desire to take France out of the European Union.

Le Pen said her party wanted a prime minister “who is respectful of National Rally voters.” She said she believes that Barnier fits this criterion but refrained from giving a blanket endorsement, claiming that the real test for her party’s support, tacit or otherwise, will depend on “how he handles the compromises that are going to be necessary on the upcoming budget.”

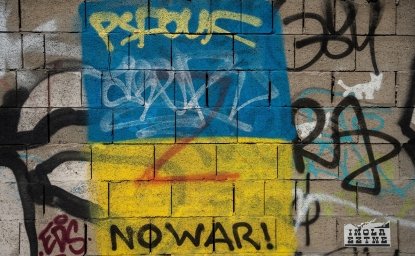

Even if Barnier is able to pull together a government that can weave through France’s political minefield, it is clear that the country’s unstable outlook is likely to persist at least until the next presidential election in 2027, when Macron will not be a candidate. That, in turn, does not portend well for strong leadership in the European Union, which has always depended on firm guidance from France and Germany to navigate the continent through difficult straits.

Author

Author "The Last President of Europe: Emmanuel Macron’s Race to Revive France and Save the World"

Global Europe Program

The Global Europe Program is focused on Europe’s capabilities, and how it engages on critical global issues. We investigate European approaches to critical global issues. We examine Europe’s relations with Russia and Eurasia, China and the Indo-Pacific, the Middle East and Africa. Our initiatives include “Ukraine in Europe”—an examination of what it will take to make Ukraine’s European future a reality. But we also examine the role of NATO, the European Union and the OSCE, Europe’s energy security, transatlantic trade disputes, and challenges to democracy. The Global Europe Program’s staff, scholars-in-residence, and Global Fellows participate in seminars, policy study groups, and international conferences to provide analytical recommendations to policy makers and the media. Read more

Explore More

Browse Insights & Analysis

Greenland’s New Governing Coalition Signals Consensus

The Future of France's Far-Right Party

Ukrainian Issue in Polish Elections